Public Honors for Secret Combat

Medals Granted After Acknowledgment of U.S. Role in El Salvador

By Bradley Graham, The Washington Post, May 6, 1996, page 1A

This text was retyped for readability and cross reference.

Worth noting: This article was published on Page One of The Washington Post, the newpaper that attempted to bring down the Reagan administration for sending arms and money to the Contras in Nicauragua in what was known as the Iran-Contra scandal (1985-87). This article reveals that the US sent not only arms and money to central America, but US soldiers. In 1996, however, the Post's attitude had changed to total approval with not a whisper of protest. (The Washington Post, May 6, 1996, Front Page) Click to enlarge.

They stepped forward solemnly yesterday across the lush green Arlington National Cemetery lawn--a wife here, a son there, several teenage children in one case, a graying father and mother in another--all to receive military service awards for loved ones who died years ago in a Central American war where U.S. forces were not supposed to be fighting, or so the U.S. government said at the time.

But U.S. troops did come under fire in El Salvador, and fired back, as U.S. authorities now acknowledge. Dozens of soldiers who were there, many of them still in uniform, watched yesterday as Salvadoran children, escorted by U.S. commandos, placed tiny American flags beside the names of 21 killed in action.

Later at an Arlington hotel, about 50 of the more than 5,000 U.S. veterans of El Salvador's civil war also were honored for service in sometimes hazardous operations for which they have never received the kinds of badges and patches normally issued to U.S. service members after combat.

"For too long, we have failed to recognize the contributions, the sacrifices, of those who served with distinction under the most dangerous conditions," William G. Walker, U.S. ambassador to El Salvador from 1988 to 1992, told the cemetery crowd. "Only today, a full four years after the achievement of peace, are we finally and officially proclaiming that those who served and those who died did so for the noblest, the most unselfish of reasons."

Just what U.S. forces were doing in El Salvador generated some of the most heated political battles in Washington in the 1980s. Determined to draw a line in El Salvador against leftist insurgents after Nicaragua fell to the Sandinistas, the Reagan administration in 1981 beefed up Special Forces teams sent to train Salvadoran government troops to fight an increasingly strong guerrilla army, the Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front.

But Republicans worried that news of U.S. troops engaging in combat in El Salvador, even in self-defense, would recall the ill-fated creep two decades earlier into Vietnam and prompt the Democratic-controlled Congress to cancel aid programs.

So critical was maintaining at least the appearance of a noncombat U.S. role that a U.S. colonel, videotaped by a TV crew carrying an M-16 rifle in El Salvador in 1982, was whisked out of the country before too many questions could be asked. Reports of firefights involving U.S. troops were closely held, and field commanders were told in no uncertain terms not to nominate soldiers for combat awards.

By the time a Salvadoran peace accord was signed in 1992 and Democrats had taken charge of the White House, there was little interest in Washington for setting the record straight about U.S. military actions in El Salvador and considerable hesitation among Army leaders about doing so. "It had been determined this was not a combat zone, and they were going to hold the fine on that," said Joseph Stringham, a retired one-star Army general who commanded U.S. military forces in El Salvador in 1983 and 1984. "I've puzzled over why. It may be something as fundamental as the bureaucracy not wanting to reverse itself.

Officially, there were only 55 American advisors in El Salvador at any one time, and their rules of engagement prohibited them from participating in combat operations. But none doubted he was in a combat zone. They carried weapons, received combat pay, accompanied government troops in the field and were targeted by guerrillas who had decided U.S. troops were fair game.

"The U.S. government was going to allow a clever blurring of the history of the civil war to go unchallenged," said Greg Walker, a former Army Special Forces staff sergeant who has led a veterans' campaign to gain official recognition of the US military role in El Salvador.

"We wanted to correct the history," Walker explained. "We wanted to recognize the sacrifices of those who served but were made to feel they were fighting a dirty secret war that no one wants to talk about. And we wanted to honor our dead and bring closure to their families."

Particularly troubling for many who knew the truth were the incomplete or outright false official reports relatives received about the circumstances surrounding the deaths of those killed in action in El Salvador.

Judy Lujan, wife of Army Lt. Col. Joseph H. Lujan, was told her husband died in 1987 when the helicopter carrying him crashed into a hillside during stormy weather. But the Army never produced her husband's personal effects or photographs of his corpse, despite her repeated requests, she said yesterday. "I can't get on with my life, I can't do anything, until I know for sure he's dead," she stated.

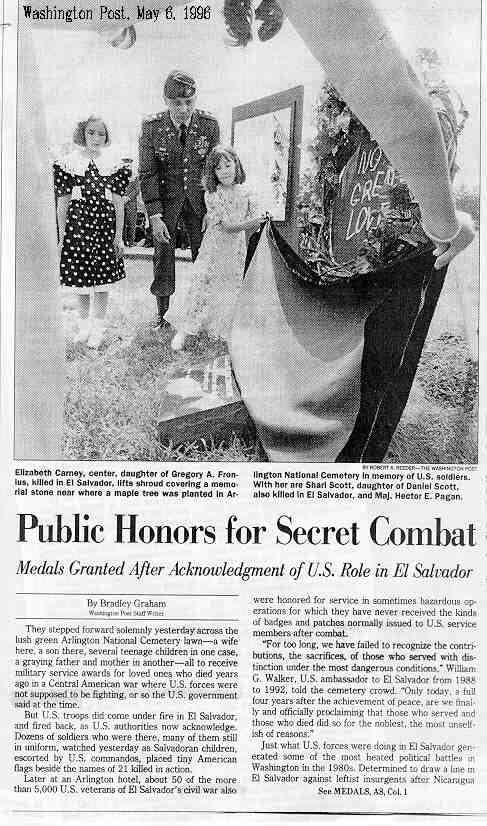

Relatives of Gregory A. Fronius, a 28-year-old Green Beret sergeant, know he was slain during a guerrilla attack on a Salvadoran brigade's headquarters at El Paraiso. But initially they were informed Fronius had died in his barracks when a mortar shell struck. In fact, Fronius had bolted from the barracks and was trying to rally Salvadoran soldiers for a counterattack when several guerrilla sappers shot him, then blew up his body with an explosive charge. "First they told me one thing, then I found out something else," said Celinda Carney, who was married to Fronius. "I was upset."

U.S. military authorities also denied Fronius a posthumous Bronze Star, ruling—as they did on other award nominations from commanders in El Salvador—that combat patches and medals could not be given to soldiers for actions in a place never recognized as a combat zone.

The turn around in the official U.S. line about America's military involvement in El Salvador came in February when President Clinton signed the 1996 defense authorization act.

A provision, pushed through by Rep. Robert K. Dornan (R-Calif.), who credits a CBS '60 Minutes' program last May highlighting the Salvadoran story, ordered the Pentagon to give Armed Forces Expeditionary Medals to all who served in El Salvador from January 1981 to February 1992.

"This opens the door for the submission of awards packages for everything from combat infantry patches to medals of valor," said F. Andy Messing Jr., a major in the Army Special Forces reserves who runs the Capital National Defense Council Foundation and made several dozen trips to El Salvador in the 1980's.

The Army bureaucracy remains slow to mobilize in support of the veterans. Military spokesmen did not advertise yesterday's awards ceremonies, which were organized, not by the Pentagon, but by No Greater Love, a nonprofit group dedicated to comforting relatives of those killed in military service, or by acts of terrorism.

Army leaders have been asked to reconsider granting medals of valor to some involved in the Salvadoran operation, but they have not decided how to proceed.

"Our challenge now will be documentation," said Lt. Gen. Theodore Stroup, who oversees Army personnel issues and was the senior ranking military officer at the cemetery ceremony. "Since commanders weren't authorized to submit all the paperwork for combat awards, some of the paper trace may be lacking But for some, at least, the book on El Salvador can be closed.

'When I told people my father was killed in El Salvador, they said we don't have troops there," Jonathan Pickett, 16, told the cemetery gathering. His father, Lt. Col. David Pickett, commander of an Army helicopter assault unit, was slain by Salvadoran guerrillas and is the only soldier killed in El Salvador to be buried at Arlington.

A bugler sounded taps over Pickett's white tombstone at the end of yesterday's remembrance.

Home: Museum Entrance

Search: Museum Text