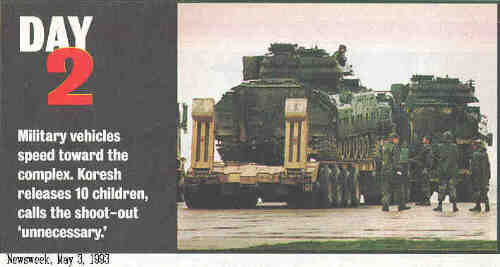

When we magnify this picture, the soldiers are clearly visible, directing the activity. In the entrance to the War Gallery, we saw that military equipment was present at the Mt. Carmel Center from Day One. Here's what they had lined up on Day Two. (Photo Newsweek, May 3, 1993) Also see The Dallas Morning News, March 3, 1993, for more equipment photographed on Day Two. |

On July 30, 1992, one of David Koresh's business associates, Henry McMahon, received a visit from several ATF agents. The subject of the inquiry was recent gun purchases by David Koresh. McMahon, himself a gun dealer, phoned David Koresh while the agents stood in front of him, and told Koresh about the ATF inquiries. Koresh invited the ATF out to inspect his premises and his guns.

According to Mr. McMahon's testimony in the 1995 Congressional hearings, when he relayed Koresh's invitation, the ATF agents declined to accept the invitation. The legality of David Koresh's guns was, therefore, never the issue. The ATF could have gone out and inspected his guns at any time.

Had the ATF not wanted to accept Koresh's invitation to come out to inspect the guns, and had they simply wanted to arrest him on some pretext, they could have apprehended him when he was out of the Mt. Carmel Center. But ATF claimed that David Koresh never left the property, and therefore a raid was necessary to apprehend him.

In an article entitled: "Residents, businessmen say Howell not a recluse," which appeared in Waco Tribune-Herald, March 4, 1993, one Waco resident was quoted:

"To say that he never leaves that place is ridiculous. He is always out everywhere. Everybody and their dog see him and many of the people out there. But I guess they are just trying to cover themselves because they are going to be in big trouble — hopefully," she said. (Waco Tribune-Herald, March 4, 1993 — archived, cached)

David Koresh used to work on car engines at a repair shop owned by the Davidians, which was about five miles from the Mt. Carmel Center. He was also "seen dining and drinking at Chelsea Street Pub, a popular West Waco eatery, at least twice in the past six weeks," according to the The Waco Tribune-Herald. There was no need for an assault, no need to endanger ATF agents, and no need to endanger peaceful civilians.

What was at issue? The issue seems to be that the February 28, 1993 raid and ensuing siege provided the US the opportunity to test, for the first time, the "National Response Plan." (Treasury Report, pg. 152 for description).

Purpose of National Response Plan

It is impossible to get a plain English definition of the "National Response Plan" from the Treasury Report. The nature of the plan and its purpose must be inferred from the obfuscated verbiage.

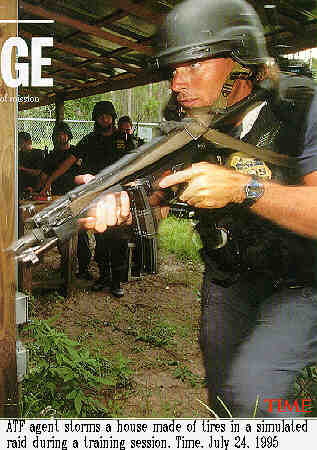

An ATF agent storms a house made of tires in a simulated raid during a training session. Time, July 24, 1995.

A chart of the National Response Plan's organization appears on Treasury Report, pg. 63. At the top of the chart, we see that control of the plan is vested in the "National Command Center," which was ostensibly under the command of an ATF agent (Treasury Report, pg. 152). At the bottom of the chart, we see other federal, state, and local law enforcement agencies, the Department of Defense (DOD), with National Guard support. Thus we are asked to believe that an ATF agent sits at the top of the organization board (in command) and that the Department of Defense is at the bottom of the organization board.

It is of course unbelievable that an ATF employee would be taken seriously if he tried to issue directives to the Pentagon concerning the deployment of Pentagon troops. The picture of a four-star general, having climbed to the top of the military chain of command through decades of careful politics, taking orders from Treasury Department functionaries is not credible. Had this organizational chart borne semblance to reality, we surely would have seen the "DOD" box at the top of the chart.

National Military/Police Take-over Plan

What was the purpose of the plan? The National Response Plan "sought to define ATF objectives, policies, and procedures to ensure a coordinated response and rapid deployment of ATF resources to situations that exceeded the capabilities of a single field division," (Treasury Report, pg. 62). According to the schema, DOD National Guard units could be called up to assist the ATF.

But the ATF is essentially a tax-collecting agency. What "situations" could exceed the capabilities of an ATF field division to collect taxes? Clearly, any situation that required the power of the DOD National Guard would be a major civil upheaval. The NRP is a preparation for armed confrontation between the US government and US citizens.

Prior to about 1999, small sectors of the population of the United States believed the Second Amendment of the US Constitution was designed to enable the people to resist the power of the government. An armed and "well regulated" (trained) populace, it was thought, would prevent the government from devolving into tyranny. The government could not enforce unjust laws against the populace if the populace were armed to resist that force. A number of groups developed paramilitary organizations, called themselves "militia," and practiced paramilitary drills.

Between nations, the contemplation of conflict often leads to an arms race. Within the US, the possibility of conflict with the general populace had the same effect on the government. To meet the threat of insurgency, the government developed riot weapons, "crowd control" weapons, and weapons of mass destruction unnecessary for conflict with external enemies. It also developed procedures and organizations capable of meeting the "threat" of a recalcitrant populace.

According to Wikimedia Commons, this photo of the ruins of the Mt. Carmel Center was taken by the BATF on April 19, 1993.

"Threat?" Yes, indeed. To the authoritarian mind, refusal to submit to the "authority" is equivalent to an attack on the authority. Once the authority engages a target, the conflict must always result in utter surrender or death of the target, and the force of authority is escalated until one of those results is achieved.

At the heart of this conflict is a question at the very heart of the US Constitution: Who is the sovereign? Does the government exist by permission of the people? Or do the people live how they live and do what they do only with permission from the government?

If the people and the government have different answers, conflict is inevitable. The National Response Plan was one of the government's answers. Under that plan, when the BATF found itself facing a situation beyond its control, it could escalate the crisis through the organizations of limited force (police) until the action reached the body of unlimited force, i.e., the US military.

Another necessary element was the control of "Psychological Operations," as it is called in the military. The government must control the news media and the emotions and attitudes of the people at large.

The Report of the Department of the Treasury outlined a part of the Plan, designed it says, to meet the threat of "terrorism," homegrown or otherwise. As with nuclear bombs, a weapon without a test is useless. The NRP required testing in the presence of real courts, real lawyers, real news media, and a real population.

First, they needed an enemy militia. The Branch Davidians were carefully selected for several features:

- They were isolated

- They were armed

- They could be demonized

In addition, the Branch Davidians were already on the national enemies list. David Koresh had divorced Christianity from a dependence on the modern nation of Israel, and he was an extraordinarily active missionary, mailing out tapes of sermons, traveling abroad, and preaching his message. He was also remarkably effective in persuading new recruits to join his movement.

Would Americans tolerate a massive troop buildup against a religious community? To meet this problem, the troops used the strategy called "false flag." If the government could appear to be the victim rather than the aggressor, all would be well with the people. Apparently, the plan was to assault the Davidians and suffer casualties. Since the Davidians might not succeed in killing some of the agents, snipers were included in the assault force to ensure casualties among the government forces, giving out the story that the Davidians had killed cops in the line of duty. And like so many false flag operations by so many other governments in history, it worked perfectly.

How the Plan Was Tested

The Waco locals were recruited as helpers in the planning. For example:

- The ATF chose the Texas State Technical College (TSTC) as the site for the command post of the operation. The sheriff's department had previously gotten cooperation from the airport manager. (Treasury Report, pg. 55).

- At the suggestion of the local police, the planners chose Bellmead Civic Center as the staging area because it was large enough to accommodate the agents, it was close to Mt. Carmel Center and had ample parking. (Treasury Report, pg. 56)

- The Texas Rangers were lined up to surround the Mt. Carmel Center and prevent anyone from leaving. (Treasury Report, pg. 79)

- The McLennan County sheriff's department was lined up to "provide other support functions." (Treasury Report, pg. 79).

-

When the raid "failed," Mt. Carmel Center was cut off from its neighbors through the

efforts of local law enforcement personnel and SWAT teams, including:

- the Austin Police Department,

- the McLennan County Sheriff's Department, and, for federal balance,

- the US Marshall's Service (Treasury Report, pg. 112).

- By March 2, 1993, 400 local, state, and federal law enforcement officers had converged on Waco ( The Dallas Morning News, March 3, 1993, "Negotiations with cult drag on: 14 may be dead in compound; Group's leader fails to give up as promised"; The Dallas Morning News, April 21, 1993, "Many officers making plans to head home; FBI dismantling command post")

- During the 51 days of the siege, the FBI sent 668 people to Waco. Each day an

average of 217 agents and 41 support people were present.

The DoJ Report, pg. 10, states that

other military/law enforcement personnel on site were:

- ATF — 136

- Customs — 6

- Waco Police Department — 18

- McLennan County Sheriff's Office — 17

- Department of Public Safety (Texas Rangers) — 31

- Department of Public Safety (Patrol) — 131

- US Army — 15

- Texas National Guard — 13.

The raid was a bonanza for the local merchants:

- ATF officials conducted a briefing at the Best Western Hotel. Attending were members of the arrest and support teams, National Guard members, explosives specialists, dog handlers, and laboratory technicians.

-

Local merchants were lined up to supply the raiders with:

- ambulance services,

- portable toilets, and

- doughnuts.

- The sheriff's department saw to it that coffee would be ready for the raiders at the staging center on the morning of the raid (Treasury Report, pg. 79).

Military Occupation of Local College

"At the central command post on the campus of the Texas State Technical College, officials set up briefing tents on the lawn. Hundreds of agents passed in and out of the barracks at the former military field, which includes an aircraft hangar and airstrip.

"Just before 11 a.m., a number of buses and heavily armed ATF agents carrying plastic flex-cuffs left the base for the compound. Dozens of agents began carrying tables, chairs and stenography machines into the hangar, students and instructors at the college said.

"Then ATF agents began evacuating the campus. Students said armed officers entered classrooms and told them to leave." (The Dallas Morning News, March 3, 1993, pg. 14A, "Negotiations with cult drag on: 14 may be dead in compound; Group's leader fails to give up as promised")

And How Did The Test Come Off?

The first test of the National Response Plan went very well, it seems.

- State and local police, from the Texas Rangers to the local county sheriff's department cooperated with the federal government.

- The local merchants enjoyed the business opportunity afforded by visitors to Waco,

- The news services conducted no independent investigation whatsoever—they simply relayed the government propaganda line. In other words, the media covered Waco in the same way they covered the Gulf War (see Veracity of Contemporaneous News Coverage).

- Civic organizations — from the American Civil Liberties Union to the Southern Baptist Conference — barely made a whisper of protest or opposition.

- The politicians in Washington DC conducted cover-up Congressional investigations (see Burial Gallery).

A police squad never flies a flag over the bodies of men, women, and children whose lives the police have failed to save. But a military unit will commonly raise a flag over people it has successfully conquered or killed. Photo, The Dallas Morning News, Feb 27, 2018, "51 days under siege", cached. Click to enlarge.

Aside from a few glitches, some of which you will read about in this Museum, the National Response Plan drill came off very well. It's too bad so many innocent Americans died as a result, of course, but those that died were not the ones making the money. It's just a question of being in the wrong place at the wrong time, as opposed to being in the right place at the right time.

In the military takeover of a country, paradigms must be established, from which the people can learn that resistance to the new order can only result in annihilation. With the practical details embodied in the National Response Plan, the new paradigm was established in Waco, Texas in 1993.

Update, June 7, 1995:

And the Tests Go On …

Since the Waco Holocaust, the US military practice sessions have become even bolder. The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, June 5, 1996, reported that "urban environment" warfare exercises have been conducted in several US cities, including Atlanta, Chicago, and Dallas.

Most recently, Special Ops exercises in Pittsburgh provoked a considerable negative public reaction. According to the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette report, between midnight and 2 a.m. on June 4th, 200 Special Ops commandos buzzed the city with Black Hawk helicopters, slid down ropes to the streets, and landed in the Brighton Heights area. They fired loud explosions and fired blank bullets for sound effects, and set off small explosions to breach doors in an abandoned building. Department of Defense Spokesmen said they were simulating a "rescue."

Notice the same Orwellian rhetoric used in Waco: This is not an assault, this is a rescue.

According to another report, one startled resident said, "If I had been up on my third floor, I could have touched it "the helicopter" with a broom handle. That's how close it came."

The 911 emergency operators were given handouts instructing them to tell panicked callers they were witnessing "training" exercises. Callers who would not be placated were to be given another telephone number that connected them to the DOD.

Some local officials had been warned of the exercises, and indeed helped in setting them up. But the public had deliberately not been warned, ostensibly to avoid the public safety issues created by curious onlookers.

These exercises are, in part, mass desensitization sessions, the object of which is to dull public reaction to the sights and sounds of military takeover of urban areas. See "The Making of a Commando" in The Black Army for a description of desensitization programs.

Visitors who have read The Boy Who Cried Wolf may remember what the young shepherd with a warped sense of humor learned: If you fake a wolf alert too often, people stop coming when you cry wolf. Now the wolf has learned the trick: It's only a drill, a practice session, I'm here to rescue you. Go back to sleep.

These practice sessions will enable the Pentagon to send a flotilla of military helicopters over any major city, day or night, land soldiers in the streets, set off guns and explosions, and breach doors with grenades — and people will ignore them.

Paul Revere may ride, but we will ignore him, too. We all know the British are just maneuvering and practicing their skills — they are just here to rescue us.